Preserving historic bee specimens to protect future bee biodiversity

-- Contributed by Joan Meiners, PhD Student, Ernest Lab, School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Florida

For my PhD research in Dr. Morgan Ernest's lab at the University of Florida, I am using large datasets of occurrence records of native bees and their habitat associations to try to understand native bee biodiversity and foraging patterns. As many people are aware, bees have been the source of a lot of media attention and public concern in recent years due to sudden, drastic, and perplexing declines in global honeybee populations that began in 2006. (For more on Colony Collapse Disorder see my 2012 post here.) Research on the well-being of this important agricultural pollinator has since become an international priority, and honeybee hives are closely monitored by experimental, industry, and hobbyist beekeepers. What is not as commonly recognized or monitored are the 20,000 other species of bees in the world that are also essential pollinators of wild and cultivated plants, but do not live in hives or make honey. While photos showcasing the beauty and diversity of some of these lesser-known species have recently taken the internet by storm, the global research lens has still not captured sufficient understanding of the ecology and stability of these important pollinators to ensure they are not also in sharp decline. One reason for this research disparity is that the solitary lives and inconspicuous ground-nesting habits of many native bee species make them difficult, expensive, and time-consuming to track. Evaluating trends in native bee communities over time, therefore, must often rely on the existence of museum records to which modern data can be compared.

Dr. Terry Griswold overseeing the museum curation process and collection display at the USDA-ARS Logan Bee Lab in Utah. Joan Meiners and Therese Lamperty collecting bees at Pinnacles National Monument (made a National Park in 2013).

I am using data collected over the flowering seasons of 2011 and 2012 at Pinnacles National Park in CA, combined with preexisting museum records from the same area, to try to understand the ecological dynamics that enable this region to be one of the most biodiverse known for bees on the planet, and whether this diversity is stable. This small (100 km2) park inland of Monterey, CA was first flagged as a bee biodiversity hotspot in the 1990s when my Master's advisor, Dr. Terry Griswold, and his previous student, Olivia Messinger, collected approximately 27,000 bees and identified 398 different species there, a biodiversity record for such a small area. These bee specimens were transported to Utah where they were each pinned, identified, given a unique barcode accession number, entered into a large relational database, and deposited into the USDA-ARS "Logan Bee Lab" museum, which houses 1.5 million curated bee specimens collected over the past century from all over the world. In 2002, a National Park Service employee, Amy Fesnock, decided to sample for bees using a passive pan trap collecting method in a few areas of the park. The 5,000 specimens from this effort were also curated at the USDA facility, and added an additional five unrecorded species to the park bee inventory.

Panorama of the namesake 'Pinnacles' rock ridge that divides the east and west sides of Pinnacles National Park, America's newest National Park in the Inner South Coast Range of California.

Because of these historic bee collection efforts, and the specimens that were retained, curated, and databased, we have a snapshot in time of the biodiversity, composition, and ecological dynamics of one of the most thriving and complex native bee communities currently known. In 2011 and 2012, I began a more systematic, plot-sampling study at Pinnacles National Park to better characterize the bee diversity throughout different habitats at the park and establish a repeatable monitoring protocol that can serve as a stronger baseline for measuring future changes in the Pinnacles bee community. My field technician, Therese Lamperty, and I collected and processed 52,000 bee specimens over these two years, and increased the species diversity number to 479 species ever detected at Pinnacles. In 2013, this exceptional bee diversity was cited as an example of the rich biodiversity at Pinnacles, which helped convince President Obama to elevate what had been Pinnacles National Monument to America's 59th, and newest, National Park (read more about that here).

I am excited that my Master's work helped to facilitate this recognition of bee diversity and Pinnacles as a National Park. For my PhD work, I am continuing to work with these datasets to understand why Pinnacles is such a haven for native bees and the differences between the museum data and my recent collections. Seventy-six of the species recorded at Pinnacles had not been detected in all five years of previous collecting. Another 126 species that had been recorded within the boundaries of Pinnacles between 1996-2002 did not show up in my collection. Whether this signifies a decline in biodiversity, simple natural species turnover, or methodological differences between the studies is one of the questions I will be addressing next, made possible by the preservation of these early bee specimens.

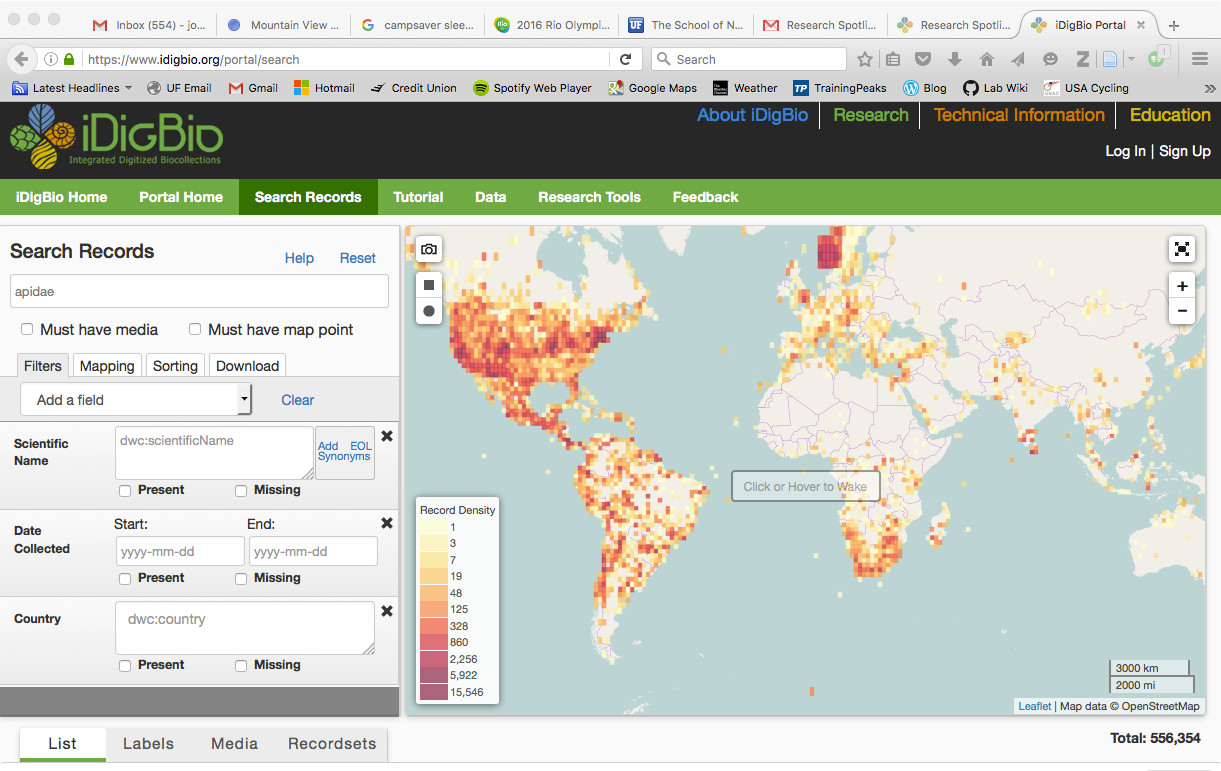

The world is worried about bee declines. We know honeybee populations have been impacted by the global threats of urbanization, fragmentation, pesticides, and climatic instability. Monitoring thousands of elusive, solitary, temporally dynamic native bee species requires considerably more time, expense, taxonomic expertise, and diligent record-keeping. But this may be the price of ensuring the pollination services of both our crops and wild lands. When attempting to answer questions about bee conservation, decline, and shifts in community species composition in relation to environmental disturbances like urbanization and climate change, historical records like those in the Logan Bee Lab or the thousands of records available via the iDigBio Portal are critical to building upon each other's knowledge to conduct better science and achieve biodiversity conservation goals.

Screen shot of search results from iDigBio's Specimen Portal site for global records of specimen in the bee family Apidae (556,354 records).

Stay in touch via:

Email: joan.meiners@gmail.com

Twitter: @beecycles

Website: www.sixlegsonecorolla.wordpress.com

Map of Pinnacles National Park boundary in green with sampling locations in red (current study, 2011-12) and blue (museum collections, 1996-2002). Squares are sampling plots from current study, triangles are trail collecting locations from current study, circles are specimen locations of museum data from 1996-2002. Incorporating organized data from earlier projects can enhance the reach and resources of newer biodiversity monitoring efforts.

Numbers of species collected in each of six North American bee families during each of seven years of collecting at Pinnacles National Park. Museum data represented in blue and green, current study data represented in red. It is difficult to discern any trend in diversity from this graph since the methods and collecting effort differed from year to year.

Relative proportion of total species in each of six North American bee families collected between 1996-2012 at Pinnacles National Park. Proportions from each year of museum data represented in blue and green, diversity additions from two years of the current study data represented in red. The original collection years detected 398 species, the 2002 study brought the total to 403, and the 2011-12 current study raised the species inventory list to 479.

Relative proportion of total species in each of six North American bee families collected between 1996-2012 at Pinnacles National Park. Proportions from original museum data represented in blue, diversity additions contributed by current study data represented in red. The current study added 76 species to the park bee inventory that had not been previously detected. We are working to understand what this difference in species captured before and after 2011 tells us about the trends and status of bee biodiversity at Pinnacles.

Relative proportion of total species in each of six North American bee families collected between 1996-2012 at Pinnacles National Park. Proportions from current study represented in red, diversity additions possible by including museum data represented in blue. The inclusion of museum collections added 126 species to the bee inventory that were not detected by the current study. We are working to understand what this difference in species captured before and after 2011 tells us about the trends and status of bee biodiversity at Pinnacles.